fr. 1

When I told Omar, a Palestinian asylum seeker, that I was just a tourist on Lesvos, staying a few days, he said: ‘welcome.’

Lesvos is indeed welcoming to tourists. Its modern and efficient airport is adjacent to the relaxed and charming port capital of Mytilene, and well-maintained roads wind through strikingly varied terrain to beach resorts, spas, picture-perfect mountain towns and fishing villages.

Omar (not his real name) had not, of course, received such a welcome. Setting out from Damascus in Syria where he was living, it had taken him a week to get here, traveling by night to avoid being caught and sent back – something he had already experienced. He was smuggled across to Lesvos on a boat from Turkey, and promptly placed in the Kara Tepe refugee camp.

He was free to leave and re-enter the camp as he wished, but also talked about the heat, disease, weak phone signal, and limited meals. Located on an exposed promontory north of Mytilene, the camp was supposed to be temporary, following a devastating 2020 fire at the notorious Mória camp - the largest in Europe - nearby. But construction of a new permanent camp, originally due for completion in 2022, is on hold.

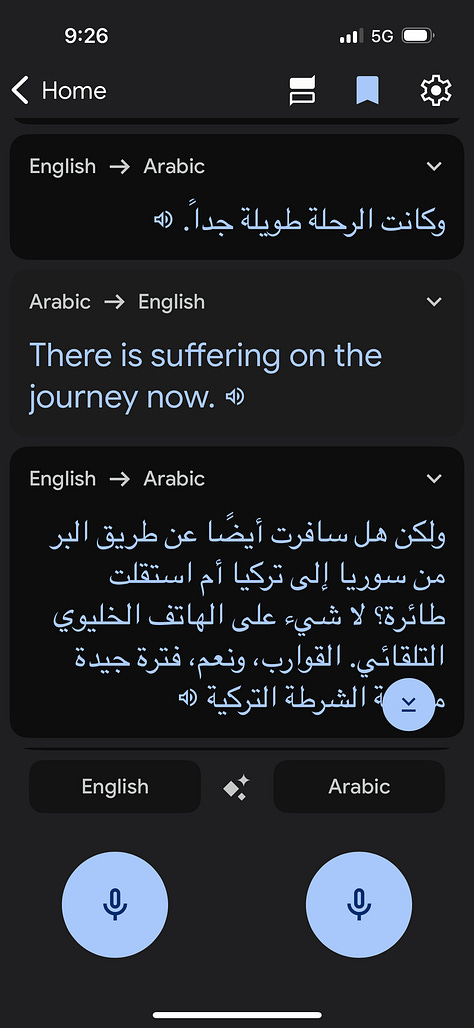

Still, Omar welcomed me. As we sat by the pretty harbour of the nearby town of Pangiouda where camp residents congregate in the evening, he offered me coffee, and we used a translation app to chat.

He had been on Lesvos seven months, waiting to hear the outcome of his residency application. He had been working as an electrician in Damascus and studying commerce. Once permitted to work, he wanted to set up a business in Greece and bring his wife and children over – he hadn’t seen them in five years.

It is not for me to say what Omar meant by ‘welcome.’ A cultural reflex, perhaps, borne in part of the basic fact that he was resident – all too resident – and I a visitor. But maybe it was anticipatory, too: a welcome spoken as much from the settled future he hopes for as in an unstable present that does not permit the luxury of despair.

fr. 2

Alongside the fishing boats common to most Greek ports and harbours, two other kinds of vessel stand out in Mytilene.

One has made it to dry land. A small rowing boat painted the colour of the Greek flags that also festoon it sits in a nook in the old Muslim quarter of the town, next to the imposing ruins of the Yeni Djami (mosque). The name of the boat is ‘Smyrna ‘1922’’. In 1919, Greece sought to press its post-World War I advantage and consolidate a territorial claim to parts of a disintegrating Ottoman empire long inhabited by ethnic Greeks. In September 1922, the campaign collapsed, leading to a massive and chaotic exodus from the burning city of Smyrna.

Smallness risks trivialising these events. In itself, the Smyrna 1922 boat is almost winsome - I am reminded of the paper boat that sailed across the stadium in Dimitris Pappaioannou’s wonderful opening ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympics, bearing its obligatory child. Athens’ National Archaeological Museum contains a 1st C. BCE statuette of a cloaked boy holding a dog. The accompanying plaque explains that it was brought to Athens from Asia Minor in 1922 and is known as the ‘little refugee.’

Surrounded by large, muscular statues, the ‘little refugee’ tag inevitably invites pathos. What it really speaks to is the relative transportability of a small statue at a time of violent upheaval.

The other distinctive boats in Mytilene bring the reality home. Lurking around the circumference of Mytilene’s large harbour are the gunmetal vessels of the Greek Navy and Coastguard.

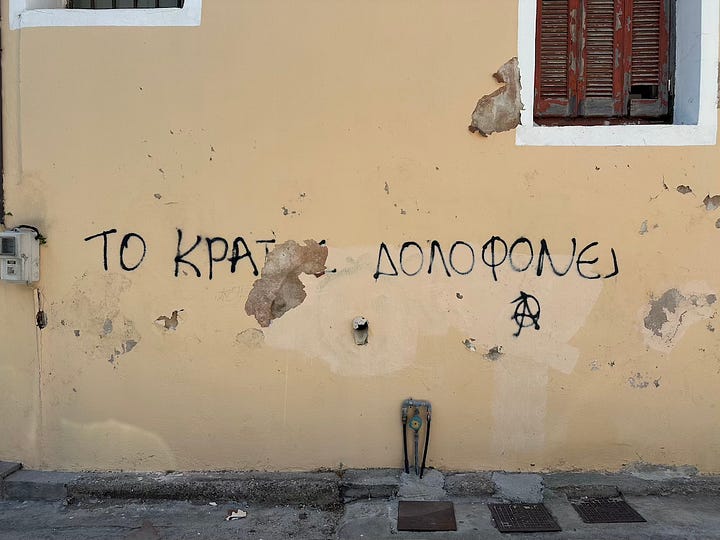

At its closest, Lesbos is barely 10 kilometres from the Turkish coastline, making Greece a ‘frontline state’ in managing refugee and asylum seeker arrivals from Africa, the Middle East, and South and West Asia. Sea arrivals have reduced significantly since their peak (according to the UNHCR, a total of 54,417 for the whole of Greece in 2024, compared to 500,018 on Lesvos alone in 2015). But the 2024 figures are the highest since 2019, and stories of pushbacks and abuses by the Greek coastguard continue to be reported. Certainly Antifa doesn’t mince words:

In 2023, the New York Times carried a detailed report showing evidence of a group of 11 asylum seekers being loaded onto a Coastguard boat and then left adrift in a raft without propulsion. The story turned on video documentation of the incident filmed by a refugee rights activist. As the report explains:

After several failed attempts by Times reporters to track down the asylum seekers, a regional public official in Izmir said that the group had been taken to a detention center in Izmir, on the Turkish coast.

Izmir is the Turkish name for Smyrna.

fr. 3

To grasp the proximity of Turkey to Lesbos, head to the theatre. Dating from the second half of the 4th Century BCE, the Ancient Theatre of Mytilene is cut into the hillside to the west of the city. You enter by a gate at stage level, with a pine glade to your left and the curved slope of the cavea (auditorium) rising steeply to the right.

On-site information about the theatre is scarce, and I mooched around the ruins for a while trying to piece it together. What kind of stage did those columns hold up? Was that hole for the base of the mechane (the crane for effecting a deus ex machina)? What was the view of the audience from the orchestra?

Almost as an afterthought on leaving, I scrambled up the cavea. Turning at the top revealed a breathtaking view completely obscured by the pines lower down. Beyond the theatre, the city; beyond the city, the sea; beyond the sea, ‘Asia Minor.’

Twenty years ago, I wrote critically about Yukio Ninagawa’s 2003 production of Shakespeare’s Pericles at the Royal National Theatre:

The actors mounted the stage from the auditorium dressed in rags and carrying suitcases, and three sumptuous hours later, they donned the same garb and left the way they had come. This trope of the ‘refugee aesthetic’, which aligns the themes of a given play and, by implication, the vocation of acting, with the generically wretched of the earth, I found to be disingenuous, to say the least. That the actors in Ninagawa’s production should enter through the auditorium, as if to represent the dispossessed Other of the audience, is a tendentious disavowal of their own privileged position (p. 20).

I was more complimentary about Neil Bartlett’s near-contemporaneous production of the same play at the Lyric Hammersmith:

There are no journeys in the play because no-one goes anywhere: at a word or a gesture, the stage is refreshed, and there they are…[A] succession of scenarios whose logic has nothing to do with linearity or location engages the audience, and presents a world that is multi-faceted, but without volume (p. 19).

This, I felt, was a more appropriate way of rendering the fantastical world of Shakespeare’s (and his presumed co-author, George Wilkins’) delirious play. In the spirit of the Chorus’s instantaneous rhetorical transportation of the audience around the Mediterranean - “And think you now are all in Mytilene” (4.4.52) - Bartlett’s dramaturgy bore greater similarity to the cyberspatial logic of the hotlink than any geographical actuality.

Now here I was gazing at a cross-section of the whole agglomeration. In Pericles, the titular character’s lost daughter is sex-trafficked into Mytilene by pirates (she talks the johns out their intentions by preaching virtue). About where that cruise liner is moored in the picture above, is where she and her distraught father are restored to each other aboard his ship.

Beyond is the sea that the American journalist Jeanne Carstensen described at the height of the refugee influx in 2015 as a “magnificent bowl of water and light [that] has become a theatre for a lethal farce.”

And in the foreground is the actual theatre: a serene monument in its own way, but essentially a ruin. Wholly open to the elements, over turbulent centuries it has become integrated into its surroundings. As an informative website explains, the theatre has been progressively looted over time, with the stones being repurposed for Mytilene’s Byzantine castle and other structures from the medieval and Ottoman periods. “However,” the website continues,

there was also extensive stone looting that followed after the [1922] Asia Minor Catastrophe, as the use of the finished building material of the theatre was offered for the immediate construction of the houses of the Asia Minor refugee settlement of Mytilene, during this difficult period in the history of the island and of Greece in general.

And think you now are all Mytilene.

fr. 4

Did Aristotle watch theatre here? It’s an intriguing prospect. Construction of the Mytilene theatre dates to the same period as his own sojourn on Lesbos from 345-3 BCE. But Aristotle was not there for theatre. His students would not set down his poetics for another fifteen years or so. Rather, as Armand Marie Leroi details in The Lagoon: How Aristotle Invented Science, Aristotle was interested in animals, particularly the abundance found in and around Lesvos’s Gulf of Kalloni, otherwise known today as ‘Aristotle’s Lagoon.’

There, as Leroi’s subtitle suggests, Aristotle spent time conducting the observations and dissections, and gathering the information, anecdotes and folklore that would form the basis of his biological writings, which make up a quarter of his total output. While he built on the work of others, Aristotle is credited with being the first in the western tradition to bring empirical methods, systematic observation and a classificatory impulse to the animal kingdom. In doing so, he developed a theoretical account of life concerned with matter, form, movement and teleology.

By that token, whether or not Aristotle attended the theatre in Mytilene is secondary to the influence of the Lesbos experience on his formulation of some of the most influential writing on drama in the west. On this matter Leroi is bracingly forthright, describing the Poetics as “a treatise on how plays work written by a biologist” (p. 349).

We can see Aristotle’s biological thinking at work both in his focus on the organic unity of tragedy, and in his classificatory approach to its component parts. Inevitably, visiting Lesvos today hardly serves up such insights whole. Rather, as is often the case for the novice visitor to Greece, it is an encounter with fragments.

I stopped for lunch at a rather windswept taverna by Aristotle’s lagoon en route to the birthplace of the famed 7th Century BCE poet Sappho. I was surprised to find no particular evidence of Sappho in Skala Eressos beyond the odd commercial venture – Sappho Real Estate, Sappho Travel and so on – but also vaguely satisfied. Sappho’s poetry has come down to us in fragment (in one case, in the belly of mummified crocodile found in Egypt in the 1870s.)

As a result her poems can begin in medias res, with an abruptness and informality that (in this translation at least), feels refreshingly contemporary:

“‘In all honesty, I want to die.’”

“But I love extravagance”

“… I urge you not to slip and fall, my dears.”

“… You’re always babbling”

And they end tantalisingly:

“But I must suffer further, worthless/As I am…”

“A handkerchief/Dripping with…”

“Neither the honey nor the bee/For me…”

“Please keep your eagerness in check,/since you have called me here, in vain,/to stab…desire…release…offspring…”

We tend to think of fragments as essentially and often irrevocably incomplete. But this quality can also lend them a distinctive plasticity: all the more mobile than lugubrious wholes, and readily insertable into any number of settings.

Sappho - 90% or more of whose works are lost - may be the exemplary instance. Her figure and verse are written on the wind. But the wind around these parts is the dry and forceful meltemi, which gusts through the Aegean from May to September. It is little surprise those fragments have traveled far and wide.

fr. 5

En route to the airport, I stopped by the abandoned site of the Mória refugee camp, which burned down in 2020. The outer wall bore the legend ‘WELCOME TO EUROPE’, with the latter word written in now-faded EU blue, golden stars recast as barbs on a barbed wire fence.

The simultaneous attraction and repulsion of the slogan on the wall of this, Lesvos’s newest ruin, reminds us that fragmentation doesn’t happen only – or perhaps even mainly – through the vicissitudes of time. It is an effect both of societal breakdown, and of systems of delineation, differentiation and control.

In the past decade, hundreds of thousands of people have exploded out of their homelands and splintered across the region, cut off from loved ones and cultural connection, hoping to create new patterns, forge new wholes.

I went to Lesvos because I had the opportunity, and because for years it had been coming at me in fragments I didn’t know what to do with: the name ‘Sappho’; Shakespeare’s Mytilene; a decade of news about refugees; Leroi’s book.

Given my trivially brief stay – three days and nights – I couldn’t not be a tourist. But if there was some complexity about Omar’s welcome to me in the harbour at Pangiouda, it was reciprocated in who it was that thanked him.

One does not accept such welcomes lightly. I offer these fragments as one way of earning that greeting.

Cue Grams: Singapore Songlist

Having spent the last couple of weeks back in Singapore, I’m including a playlist here.

I still haven’t got my ‘liner notes’ quite right, but I’m going to take that as indicative of the diversity and complexity of the Singapore cultural landscape – something I’m grateful that the irrepressible efforts of Singapore’s musicians past and present have reconnected me with.

I can’t imagine anyone else will like all these songs. And, dear citizens of Singapore, no doubt you have some better ideas! But pop the playlist on shuffle and something appealing is bound to come along sooner or later.

We start out with an overture of sorts, courtesy of Vedic Metal group Rudra in devotional mode (to be fair, it’s not wholly representative of their usual style), then a sutra-adjacent track from a musical by theatre company W!LD RICE cues up a flurry of showtunes, film songs (ranging from Malay film icon P. Ramlee to the Getai film 881), and warm-hearted duets and ballads. Making your peace with sentimentality is one of the most interesting things about listening in Singapore...

With The Observatory, we hit something of an indie seam. The Zircon Lounge track is more tender than it first appears, and features the late, lamented X’Ho singing in Thai.

This in turn underscores not only how multilingual the Singapore songscape is, but how much regional collaboration is underway elsewhere in the list (Tamil rapper Yung Raja’s playful collaboration with Indonesian Ming Ling is a good example - and now I think of it I realise a wholly Malaysian track has snuck in, but I’ll leave it there, without telling you which it is).

Electrico arguably exhausted Singapore's good indie ideas (though Gentle Bones and Ben Kheng give it a sunny pop spin): cue the OG Singapore Idol winner Taufik Bautista to R'n'B us into a hip-hop sequence, where some of the most interesting energy in Singapore music is right now - ShiGGa Shay’s 10-year old ‘Tapau’ (‘takeaway’) sounds serious, but as the video below shows, it’s a wonderfully playful spin-off from a feature film, 3688. ‘Oracle Bone Script’ by Mary Sue and Clementi Sound Appreciation Club is a more recent mash-up of the kinds of sound worlds you can find yourself moving through in Singapore, willingly or otherwise; and Fariz Jabba and Yung Raja as cheeky as it is inventive.

All this funkiness is brought to a screeching halt by the unreconstructed Singlish punk of CB Dogs (for those unfamiliar with Hokkien profanity, let’s just say the name alludes to, well, a Hokkien profanity).

weish’s ‘Horizon’ is startling for being a state-sanctioned National Day song, and is also a good example of an emerging trend, led by women, in inventive Singaporean version of hyperpop (also represented by UK-based Yeule, here in uncharacteristically upbeat mode, and local breakout Jasmine Sokko.)

We dial things down with Dick Lee’s ponderous version of his ‘Fried Rice Paradise’ - a musical number better known in its more upbeat iteration - and the brief and beautiful ‘Anggerik Singapura’ (‘Singapore Orchid’), from a musical revue by W!LD RICE about the iconic composer Zubir Said.

That’s the right note to close on. So I couldn’t resist wrapping up with a coda you can take or leave: the hook at 35s in Boredphucks’ multi-lingual, expletive-laden punk anthem and the crowd reaction get me every time. They were such a breath of fresh air in the claustrophobic late nineties. They still are.