There are many reasons for falling asleep at the theatre, though boredom is rarely one of them. I have napped through thoroughly enjoyable performances, and gone insomniac through real howlers. Nor is the upholstery a reliable predictor. Lay me in a recliner at Manila’s Centrestage – a former cinema with plush chairs to match – and I’m all eyes; perch me on a bum-numbing bench at Shakespeare’s Globe, and I’ll be braining myself on the balustrade of the Wooden O before the Chorus has reached the couplet.

That said, I must confess to falling asleep in the theatre more deeply and often since the beginning of this year. One reason is opportunity – having spent the past four years in a time-consuming leadership role, now relinquished, I’m playing catch-up. I’m watching as much as I can, and naturally finding much to doze to in the process.

But it turns out there’s motive as well as opportunity. Even controlling for the dreary variables of age and indolence, I now discover, as I come around in theatres large and small, local and overseas, that my leadership stint has left me bone tired. It’s an exhaustion you can’t just sleep off; one lie-in’s not going to cut it, and if a restorative slumber through a blockbuster musical could dispel it, I’d be nestling into my neck pillow at Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat as we speak.

Perhaps it’s not so much that theatre has been putting me to sleep, as that it has diagnosed my condition. My repeated and extended exposure to darkened rooms, at precisely the settings which combine relaxation of body and focus of mind, has provided theatre with a high resolution scan of the state of my audiencing consciousness.

And as with all sensitive imaging machines, this one shows not only that my sleep resistance is low, but there are comorbidities: not all theatre sleeps are the same.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Theatre knows sleep, in all its variety. At some level, all performances are dream sequences, and like its vapourous cousin the ghost play, the dream play is a genre of its own, found across time and in many cultures.

Naturally, there’s theatre for the tired – as well as the sub-category, familiar to the tourist and international researcher, of theatre for the jetlagged. There’s the accidental sleep, where you close your eyes to listen more intently, and drift off.

There are also performances where sleep is assumed. It would feel downright wrong, for example, to remain consistently alert through an all-night Indonesian wayang kulit (shadow theatre) performance. The tradition, in the days following, of the performance sponsor delivering a bowl of bubur sumsum (bone marrow porridge) to the dalang (puppet master) to restore to their body the nutrients the event took out of it is indicative of how depleting such an experience can be for all of us.*

No doubt there are other genres of theatre sleep. Equally, though, I’m interested in the possibility that we might all have a specific vulnerability – that for each of us there’s a particular form that works as our theatrical temazepam.

In my case, it’s the murder-mystery plays of Agatha Christie (1890-1976).

For the past decade or so I have been trying to make it annually to Christie’s zombie hit The Mousetrap at St Martin’s Theatre in London, where, excepting a break for Covid, it has run continuously since 1952. There have been a few impediments to my streak – living on the other side of the world, Covid travel bans, and so on. But the odd missed year is almost moot, given that I’m yet to make it through a single such performance with my eyes open.

The same went for a recent production of Christie’s And Then There Were None, which I attended (if that’s still the right word) in Melbourne.

Why?

The sniffier kind of theatre scholar, who wouldn’t be caught dead in a Christie murder-mystery, might only shrug – what else could be expected from this very definition of the formulaic and the middlebrow?

Again, though, it wasn’t boredom, which is its own state, defined in part by the inability to sleep when you want to.

I can think of two possible explanations. First, it is the logical response to a kind of informational over-stimulation. While, for obvious reasons, I can’t bring myself to agree with this reviewer that “there’s something so exciting and thrilling about [Christie’s] formula that it never fails to get audiences inching towards the edge of their seats”, the basic instinct might be correct.

In And Then There Were None, the introduction of ten characters in quick succession, along with a trawler of red herrings, may be gripping for others. In my case, it produces a defensive swoon. By the appearance of the third character, I was out like a light, only to wake with a start at the close of Act 1 when the first victim rather noisily expired upon the shagpile.

At the same time, I also can’t bring myself to agree with other reviewers, who variously described the production as ‘a museum piece’, or one that offered ‘good old-fashioned escapism’, without ‘much complexity beyond a deadly plot.’

For this Englishman at least (b. 1973), ‘an Agatha Christie murder mystery’ is only a thin veneer over a profound and troubling staging of the social unconscious I was born into. The fact that the offensive original title of Christie’s source novel was drawn from a minstrel song and remained in use in the UK until 1985 is only the most obvious way in which Christie’s work embodies the social mores of an earlier time.** But the continued popularity of the work speaks to a collective inability to break with that period.

Race, class, gender and sexuality parade phantasmagorically across Christie’s stages in ways that are bewilderingly and chillingly quickened by guilt and death. Christie’s plays are waking nightmares, in which characters struggle Britishly to maintain sanity and civility while assailed by ever more atavistic threats. This means they are best consumed in sleep: I am not missing those productions in my narcolepsy – I am matching their method with my own.

I recently learned the converse can also be true.

I fully expected to sleep through Pina Bausch’s celebrated dance-theatre work Café Muller (1978) last week. It is, after all, a performance that wears its dreamstates on its sleeve. One way of describing it would be to place each of the characters at a different stage in the sleep cycle, from one who is almost comatose, through to others whose subconscious needs and desires are constantly thwarted by their inability to gain purchase on each other (as in the sequence below), to others beset by the fluttering anxiety that hovers on the edge of waking.

This is only one way of talking about this rich and complex performance, however, and now is not the time to go into all the others. Suffice to say I got no shuteye whatsoever in Café Muller. It being so flamboyantly oneiric, the only thing I could do was pay it my full, conscious, attention.

___

*Thanks to Miguel Escobar Varela for this morsel - Miguel and I presented a dalang with just such a dish after an all night performance in Jogjakarta in 2013. As Miguel points out, the ‘bone marrow’ is symbolic: it’s actually made of sugar, rice and coconut milk.

**You can find that title on Wikipedia.

***

Picture Essay: Curb Your Enthusiasm

I’m traveling, hence the late appearance of this newsletter.

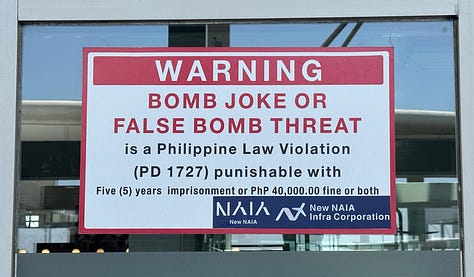

Arriving in the Philippines on Friday, I was struck by the evidence of Filipino loquaciousness and its regulation. Some of the written exhortations to pipe down are quite winning: don’t be an over-excited conversationalist in the lift; don’t go thinking dumb jokes about bombs on planes are funny; shut up and listen, you might learn something; here is a place to talk to God.

All the SIM cards offer unlimited data – price varies only by how many minutes you want to talk for, too - and once you’ve exhausted your battery, here’s a charging station.

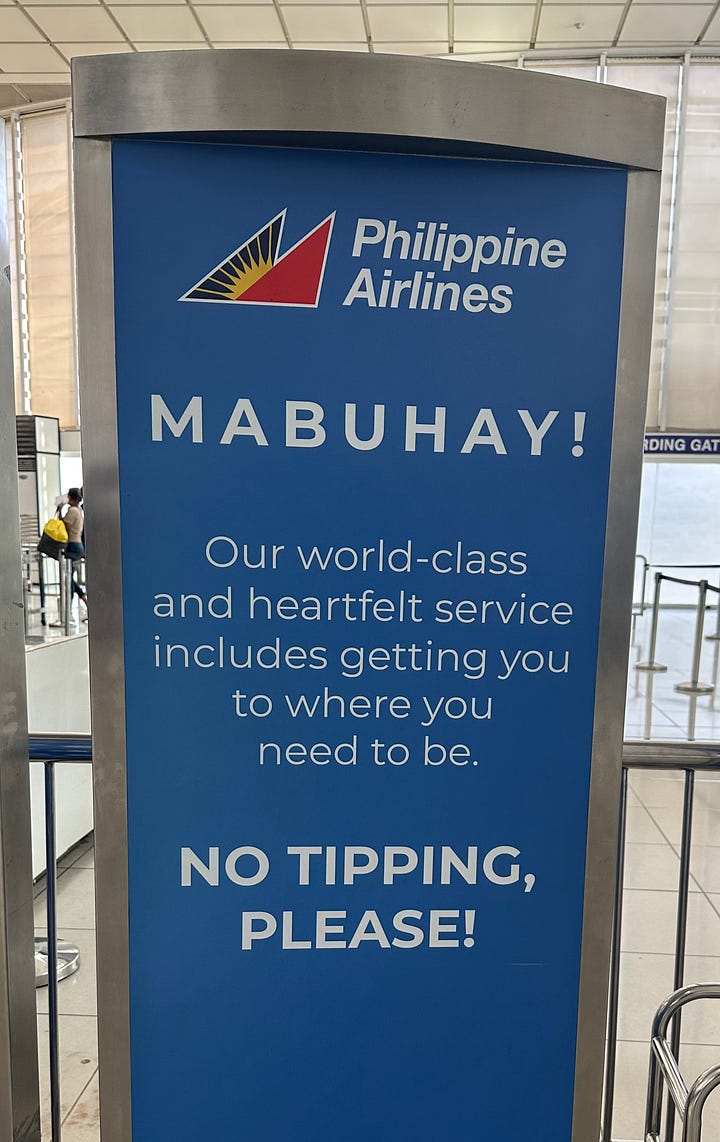

Then there are the verbal contracts or rituals woven into everyday transactions - pay by cash, and the server announces “I receive 500 Pesos…I return 250 Pesos”, and so on - and their regulation: I don’t know if Philippine Airlines’ ‘no tipping’ rule is a sincere expression of service-oriented commitment (as the attendant explained to me), a virtue-signalling bid at same, or an anti-corruption drive.

These are some of the nuances that preoccupy the contributors to a new special issue of the Philippine Humanities Review on ‘Speech Communication in the Philippines Now.’

As issue editors Oscar T. Serquiña Jr. and Charles Erize P. Ladia write in their introduction:

The term “speaker” or “communicator,” as the articles here attest, no longer simply references a figure on stage delivering a ready-made spiel or speech with unimpeachable memory and mastery; instead, it also accounts for anyone and everyone producing, disseminating, and receiving a message or a stimuli in whatever form - lingual, pictorial/photographic, corporeal— in order to obtain a response, whether overt or implied, to register an existence or leave a trace, and to institute, affirm, or shake up certain orders or relations of things (ix).

My fleeting experience at arrival points to a world of everyday verbal and gestural exuberance that exasperated authorities are struggling to keep a lid on.

Except when they’re not. Stopped from entering the wrong terminal for my connecting flight, the security guard couldn’t help serenading me with a snippet of the Bonnie Tyler classic: “Turn around, bright eyes…”

The charmer.

***

Cue Grams #3

I love this first track by guitarist Jules Reidy. They’re offsetting the basic melody with a detuned guitar (or something like that) that rubs all the sounds up the wrong way, and is also quite lovely. To my untutored ear, I recognise both western melodies and pentatonic tones that sound Chinese. A Chinese music afficionado would no doubt disagree. Perhaps better to say that this is what it sounds like when I’m trying to tune into Chinese music, with my western ear.

Accordingly, and given I’m back in Southeast Asia for the first time in a while, the rest of the list is a mix of rogue uses of Southeast Asian sounds, and their sources.

I don’t know why the American singer Circuit des Yeux (Haley Fohr) begins her song ‘Do the Dishes’ with what sounds like the Lao/Isan bamboo khaen, but she does, and then takes it elsewhere. It’s the relationship between where it starts and where it ends that’s interesting.

Only fair, too, that it’s answered with one of my favourite songs from northeast Thailand - it sounds wonderfully flirtatious, but I might be completely off-base - and followed by the soaring and velvety voice of Thai singer Phloen Phromdaen (1939-2024). If I could sing like him, I could die happy.

When I first listened to this song on a compilation a few years back, something in the voice sounded familiar. It turns out a different Phromdaen song – Klua Duang – had been comprehensively sampled and mangled by nihilistic psychopunks The Butthole Survers in the late eighties on ‘Locust Abortion Technician’ – an album I circumspectly owned, and would listen to with equal parts exhilaration and fear. Their ‘Kuntz’ is here.

Melbourne-based Balinese group Gamelan DanAnda has a new album out and I include here a brief essay in what can otherwise be a twenty-plus minute kecak chant, accompanied, unusually, by the Javanese-Australian singer Ria Soemardjo. I don’t know what the kecak is doing in Malaysia-born and China/Taiwan-based DJ Tzusing’s banger ‘Face of Electric’, but there it is.

If you make it this far, we return the earth to its axis with a longish piece by Lou Harrison (1917-2003). The combination of gamelan and western classical traditions is more musicologically complex than I can parse. Suffice to say it is one of the most beautiful pieces of music I know.

***