A Life, in Theatre

+ 'you were made for these times we live in' + a decelerating playlist + a coronation.

When I unearthed these photos from a box offloaded by my mum, the mid-eighties normcore was not the most shocking thing about them. Yes, that’s me in the Reeboks, and yes, those were my actual clothes. Or so I told myself. Because try as I might, I had no recollection of what the pictures showed. I appear to have been in some sort of play. But those experiences were among the most memorable of my youth. So what was this one? Who was I? What was happening to me?

A bit more digging turned up a programme for ‘The Magnificent Seven ’87’ in which I apparently played ‘John’. Then it dawned on me. I’d been cast as some kind of gimp. My job was to be bullied by the ‘Banditos’, here translated from the Mexican village of the source film to a ponchoed girl gang in an ‘inner city school’ (quite exotic enough, given we lived in a small regional town).

First I got roughed up, then Good-Samaritanned by ‘William’ (an Adidas-shod Martin Welton, who has been performing pretty much the same consoling function ever since). And as I glanced through the cast list of the Banditos, I realised that not only was I bullied on stage, but that same group had also bullied me off. Maybe it was the Reeboks - perhaps the Method gone rogue. But they made that production hell.

In the larger scheme of things, it was a very mild kind of trauma - just enough to produce amnesia in lieu of the usual happy memories.

The American avant-garde writer and director Richard Foreman suggests that art can ‘spin its web in the void’. Contesting the widespread assumption that the defining ingredients of any theatrical event are performers, audience and place, Foreman writes:

When a huge audience seems to be watching, it may be only a mass collection of habitual responses planted in the seats of the theatre. When nobody seems to be watching, perhaps an invisible god has his eyes on the performance.1

Can the same be said of performers? Had I been reduced, by way of self-preservation over the course of an unpleasant rehearsal process, to a ‘collection of habitual responses’ on stage? One that left no room for subsequent recollection?

Perhaps so. But this is not a pity party. If anything, the opposite: just because you’ve repressed something doesn’t mean it wasn’t formative, and what I’m really interested in here is theatre’s existence, and persistence, despite our personal investments or experiences. A certain indifference, we might say, even as theatre only keeps going by passing through our bodies.

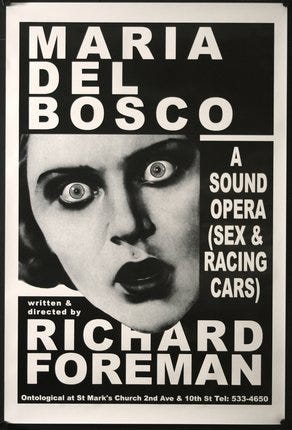

Foreman’s death this January at age 87 sent me back to an interview I conducted with him in 2002 for a preview of his production Maria Del Bosco at the Singapore Arts Festival.2

He was one of those people who gives answers in paragraphs: lucid, nuanced, perfectly formed. In part, this is because he was practiced - there’s a similar patter in many of his interviews.

But he was not just slick. He had an uncommonly refined sense of the life, even in the midst of living it. It helps, perhaps, that he led - or appeared to lead - a refined, if not privileged, life. This included a precocious childhood, a continuing commitment to the sixties as a moment of radical creative ferment, connoisseurship of high art, and a polite but firm resistance to being drawn on the meanings of his compelling but confusing work or the social relevance of art in general.

In other words, Foreman told a good story about the theatre he made with reference to the life he lived, without ever suggesting the theatre could be explained by his biography, or indeed reveal anything about him as an individual. An audience member might draw a different conclusion, but that would be on them.

Maintaining such a position seems obvious, but it’s harder than it looks. In interviews like this one, Foreman has to do a lot of deflecting to avoid anchoring his answers in his personality or psychology (as an actor, his co-interviewee Willem Defoe can’t or won’t deflect, but is engaging nevertheless).

That said, one shouldn’t need to be a modernist auteur to account for the relationship between theatre and life without collapsing one into the other. Theatre itself has plenty of insight to offer here, and most theatre-goers or -makers can probably think of plays or productions where the staging of life supersedes the representation of its living.3

The first thing that springs to my mind is Stella Kon’s 1983 Singapore classic Emily of Emerald Hill: while the narrative races through the titular character’s life, the pace and structure of the play disclose its underlying meanings and motivations. Or there’s the shenanigans of all those Chekhov characters, struggling to gain purchase on their own lives at moments when historical forces and other people are siphoning off the vital energies they previously relied on to keep going.

Other media can also capture something distinctive in this dynamic about theatre, precisely because they are not theatre.

I sometimes joke about being a theatre lifer, but the recent film Sing Sing, about a prison drama group, turns on what theatre is, for lifers. Interestingly, this is not apparent in the film’s nauseating trailer, whose relentless uplift completely betrays the nuances of the performances and the filmmaking.

The trailer suggests a film that is merely life-affirming (and an audience in the market for that); the film itself shows men tangling with the volatile energies of theatre when it enters confined lives. That idea is given a bit more of a workout in this scene breakdown by actor Colman Domingo and director Greg Kwedar, though even here the redemption narrative looms disproportionately large:

(NB: no need to watch this 10 min film to read on!)

Perhaps, in the larger scheme of things, it is when theatre is at its least imposing that it finds its proper place and weight in a life.

Although the central character and narrator of Alan Hollinghurst’s 2024 novel Our Evenings is an actor, theatre’s role is intriguingly opaque. Regular allusion is made to a mixture of actual and fictional figures from the mid-to-late twentieth century British theatre - excruciatingly, one invented director boasts that the legendary Peter Brook had come to watch his experimental Titus Andronicus in the English seaside town of Margate and ‘very much seen the point of it’.

But theatre is mainly the vantage point from which Dave Win - queer, of mixed white and Burmese parentage, and the recipient of a philanthropic scholarship to a 1960s private education his dressmaker mother could otherwise not afford - looks out upon the world as he moves through life.

On a childhood vacation:

That first night on holiday I felt a prey to waiters, all settled into their parts in a way I wasn’t; it was raw contact dressed up with rigmarole and a raw charm they could easily withhold.

During an early sexual encounter:

I hardly knew, beyond the basics, but I took on the role, I sat on the edge of the bed, and had him kneel in front of me, where I could also admire him from behind in the wardrobe mirror. At first I avoided colluding with my own expression, but it took on an undeniable interest as things got more serious.

On a racially charged ride on the London Underground:

[I]n my own trance of exhaustion and discomfort I saw oddly clearly the potential of the scene, the tired, short-tempered hatreds and fears that were ready, at another fierce jolt of the train, to kick off.

Thinking about his schoolmates as he revisits an old school yearbook:

Andrew declared himself [gay] early, I stayed years longer in disguise – the clever but involuntary disguise of being already conspicuous for something else [his ethnicity].4

Dave often feels – is made to feel – out of place. It is theatre that lightly but persistently grounds his observations of people and places (and people in places) and which, absent any central plotline, drives a story that, over time, grounds him. Beyond the theatrical analogies (roles, scenes and so on), what really suffuses the novel is a theatrically-informed mode of relating and way of seeing through which Dave emerges in relief, with growing clarity.

Hollinghurst’s evocative but unassuming title gets at the subtlety of this. ‘Our evenings are rarely our own’ says Dave of actors, who work anti-social hours relinquishing something of themselves so audience members get to live their best lives at leisure, in enjoyment and stimulation.

But elsewhere in the novel, ‘our evenings’ describes time Dave spends with his mother and, later in life, a partner. Theatre is just one way he and others spend their evenings over time. It is a presence in his life, but not a focal point.

That Hollinghurst can use the novel form – and more specifically, the sentence; boy does he know his way around a sentence! – to tease out a life more inhabited than defined by theatre speaks to the diffuse ways theatre does its thing over time, and can come, if only glimmeringly, to be known.

It would be nice if this newsletter could do something similar. That may seem a rather precious project, based on an over-subtle distinction between life and the living of it. But then this is a moment when lives are at stake, and life is in question. The actions of the democratically elected President of the United States of America since his inauguration last month stand to shorten, cheapen and degrade lives the world over. Today, that same individual was elected Chair of the Board of the Kennedy Centre for the Performing Arts.

Finding ways, within our domains of expertise, to explain what we really mean by ‘quality of life’ - its sources and component parts - is not enough in itself to counter this chilling mix of death-dealing and kulturkampf. But it’s not nothing, either.

No one has the right to bully the theatre out of us.

***

Occasional Address

In December 2024, I delivered a graduation speech - called, in university parlance, the ‘Occasional Address’ - at one of the Faculty of Arts graduation ceremonies. Taking place in the grandiose Royal Exhibition Building and with a captive audience of 1500 or so students and parents, I thought I’d use the opportunity to do some Theatre Studies…

I’m thrilled to deliver this speech. I’ve attended so many graduation ceremonies, but this is the first time I’ve had the chance to come up here and say out loud what my esteemed colleagues and I are normally sitting at the back there thinking to ourselves: “Why didn’t you come to our lectures?”

Oh, and also: “You made it! That’s so great. What an amazing achievement!”

I am also thrilled to be here because I am a Professor of Theatre Studies, and I get to remind you, in my professional capacity, that there are so many ways of thinking about what an event like this is made of, what it means, and why we are all here.

We might note, for instance – and here you can see I am taking full advantage of having a captive audience to deliver the lecture of my dreams – that many of us are wearing costumes, that there is a beginning and a middle and an end to this (don’t worry, there is an end to this!), and that there is a stage on which you each will individually appear before an audience.

This risks making it sound superficial – like it’s ‘just’ a performance. Take it from Professor Paul (and by the way, did I mention I’m a Professor of Theatre Studies?) – it’s the opposite. Many of you have given careful thought to your appearance because the moment is important – I’m not the only one here who had my hair cut last week. Some of you are also wearing symbolic items that underscore the distinctiveness of your achievement to your community, or make a political statement, or both.

Personally speaking, I get a kick out of the shoes. Since everyone’s basically wrapped in the same gown, special thanks to those who decided to really work the footwear angle.

And what’s especially great is that this individuality dovetails beautifully with the actions of the thousands upon thousands of graduands who have appeared before you on this stage, and the many more who will follow.

It’s repetition with a difference: that’s the power of ritual, and one source of the meanings of today.

Then there’s this place – the Royal Exhibition Building.

Built in 1880 to showcase the arts and industry of the then colony of Victoria, in 1886, a thousand members of the Chinese community staged a procession and theatrical performances here to raise funds for a women’s hospital. In 1901 it hosted the opening of Australia’s first federal Parliament, and in 1907, the first exhibition of Australian women’s work. In 2021, I had my Covid jabs here, as some of you may have done – almost exactly 100 years after it was used as a fever hospital during the Spanish Flu pandemic.

Gazing down upon these and countless other moments in the passage of recent history are murals with titles like ‘The Arts Applied to War’ and ‘The Arts Applied to Peace – I know which I’d choose – and also the motto Aude sapere - dare to be wise.

Do you?

When the building opened in 1880, one journalist wrote of the unprecedented view from the dome promenade: ‘everything has a new and bewildering look, well-known localities having lost for a time all their points of identity.’

That sounds to me like a good description of a university education, at least to begin with. That’s where the ‘daring’ part comes in – stepping up to take a global view and lose your bearings. The ‘being wise’ part lies in the new sense you make of what you thought you knew, once you come back down to earth.

And here you are. Not only with your feet on the ground, but feeling, perhaps, the weight of hope and aspiration resting on your shoulders; to which Professor Paul has now added that of ritual and tradition. Oh, and also a colonial and national history we should not receive uncritically.

It can feel a little daunting. But here’s the amazing thing. No one carries so much and yet wears it so lightly as a graduating student like you. At this podium in August, the celebrated Indigenous novelist Alexis Wright said to a previous cohort of graduates: “You were made for these times we live in.”

I think what she meant was this: even as we carry the weight of a complex history into an uncertain future, no one is better qualified than you to face it. Of all the people in this room, you are the ones with the greatest potential: you have the latest knowledge, the most energy, and the fewest constraints on what you’ll do with it.

So you may imagine you are sitting there in one long queue, waiting your turn. You are not. You are here to appear before us, one by one, and the rest of us are here to be present to each of you in recognition of everything you have achieved and are yet to create.

After that, and a nibble on a sandwich upstairs, you will stride out of here in your amazing footwear, and strut your stuff in the world. Walk tall, my friends, however that applies to you, and congratulations on graduating successfully from the University of Melbourne.

***

Cue Grams

I’m guessing ‘cue grams’ is what stage managers used to say when gramophones were still in use. I’m no theatre historian, but I do know it’s what long-suffering SM Madge says in Ronald Harwood’s 1980 play The Dresser, set in the 1940s. Anyway, it seems an apt featurette title for a few listening recommendations.

NB: To give the artists their due, I’ve linked below to official channels wherever possible, with a Spotify compilation of the whole playlist below (and here.)

Sometimes it’s whole albums. Recently, it’s particular songs I’ve been going back to, and here’s a decelerating selection. We start at a jaunty angle with a playful track from Doechii featuring some perfectly pitched dialogue and delivery. SOS by Khadija Al Hanafi keeps pace, but is as minimal as Doechii excessive. Then it’s riotous self-empowerment courtesy of the Lambrini Girls’ Cuntology 101. Near the mid-point we hit the best song Blondie never wrote thanks to Sharon Van Etten, before taking things in a darker direction with Voice Actor. Then we really start applying the brakes. It was tempting to include one of the two properly punishing Ethel Cain tracks that sandwich Punish on her new album - slow, indistinct, and unsettling. But hey, we’re still getting to know each other, and ‘Punish’ repays careful, committed listening in half the time. Having kicked off with a dialogue, we wrap with a duet, though that may be as far as the similarities between the Doechii and Bòsc’s mournful Complainte go. By way of coda, we float off into the ether with Ulla’s barely-there macys.

***

Theatre in the Wild

Reports from the archive.

Foreman, Richard. ‘Foundations for a Theatre’, in Krasner, David (ed.), Theatre in Theory 1900–2000: An Anthology (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), pp. 489–93 (here, 493).

For the curious or the suspicious, perhaps it’s worth mentioning that here I’m no doubt too casually channeling a distinction made by the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze between the life (of an individual) and a life (an ‘impersonal and yet singular life’ out of which individualization periodically emerges and causes the individual to recognise themselves as such.) As may already be apparent, Deleuze’s account of a life is rather involved. The clearest he gets in explaining it is this: “A life is everywhere, in all the moments that a given living subject goes through and that are measured by given lived objects: an immanent life carrying with it the events of singularities that are merely actualized in subjects or objects.” But this in turn is tied up in a larger argument about the ‘plane of immanence’ - not a place I hang out if I can help it. (Though if you’d like to, see Deleuze, Gilles. ‘Immanence: A Life’ in Pure Immanence: Essays on A Life. Trans. Anne Boyman (New York: Zone Books, 2001), pp. 25-33; here, p. 29).

Hollinghurst, Alan. Our Evenings (London: Picador, 2024), pp. 105, 287, 359, 452.

“theatrically-informed mode of relating and way of seeing through which Dave emerges in relief”

I loved this, left me thinking of ways in which this informs how I do my research/writing.

Also, that deep breathing exercise at the end of the Doechii song makes me ascend. Have you seen the video?

I loved this! Especially as I’m writing about Hollinghurst for my dissertation.